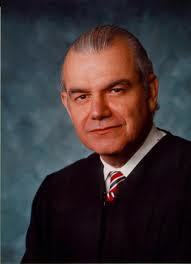

After a five-year summary judgment battle in a federal asbestos Multidistrict Litigation court, District Judge Eduardo Robreno has granted a defendant’s move for summary judgment based on the bare metal defense and poor product identification.

Robreno granted defendant Viad Corporation’s summary judgment in a March 13 order.

Plaintiff Theresa Schott’s lawsuit was transferred to MDL asbestos docket 875 in March 2009 from the Central District of California. By November 2009, the legal battle on summary judgment began.

Schott alleges her husband, Robert Schott, was exposed to asbestos while serving in the U.S. Navy as a fireman and machinist mate aboard the USS Moore from 1959 to 1966.

Robert Schott later died of mesothelioma, allegedly as a result of his work with gaskets, packing and insulation.

Schott contends Griscom-Russell Company (GRC) manufactured an evaporator used on the ship that contained the asbestos insulation and gaskets that allegedly caused her husband developed mesothelioma.

However, Viad, the alleged successor-in-interest of GRC, moved for summary judgment on the grounds that there is insufficient product identification evidence to support causation. It says it is entitled to the bare metal defense and claims it is not the corporate successor to GRC.

Then in November 2009, the MDL court referred the case to Magistrate Judge Thomas Rueter, who then issued a report and recommendation in July 2011 stating that summary judgment should be granted. He ruled that there was neither direct nor indirect evidence proving Robert Schott worked with or was exposed to any original or replacement asbestos containing parts on the evaporator that were manufactured or supplied by GRC.

The claimant objected to the report and recommendation, claiming it failed to credit a plaintiff expert who allegedly shared facts referring to the defendant’s product identification and causation grounds.

Robreno examined Rueter’s report and recommendation and Schott’s objection to make a decision on summary judgment.

Regarding this particular case, the parties allege that California law applies. However, Robreno found that maritime law is proper because the claim meets both the locality and connection tests.

According to the locality test, the tort must have occurred on navigable waters or have been caused by a vessel on navigable waters.

The connection test requires that an incident could potentially disrupt maritime commerce and that the injury shares a substantial relationship to traditional maritime activity.

“It is undisputed that Mr. Schott’s alleged exposure to GRC product(s) occurred during his service in the Navy while aboard a ship,” Robreno wrote. “Therefore, this exposure was during sea-based work.”

Robreno notes that Rueter analyzed the instant case under California law rather than maritime law, but the result did not change.

Therefore, under maritime law, the “bare metal” defense is recognized. It determines that a manufacturer is not liable for harms caused by a product it did not manufacture or distribute and has no duty to warn about hazards associated with those third-party products.

In other words, “bare metal” products relate to those that contain or were encapsulated in asbestos-containing products made by a third party. The arguments raised from this type of exposure refer to it as the “bare metal defense” in litigation.

Viad argued that the plaintiff failed to provide evidence sufficient to establish causation and that it has no duty to warn and cannot be liable for injuries arising from third-party products.

However, Schott argued that her husband removed insulation and gaskets from the GRC evaporator “many times,” which allegedly resulted in breathable asbestos dust.

The plaintiff provided testimony supporting the claims by the decedent and co-worker Richard Withers. Captain William Lowell also gave an opinion supporting the claimant’s argument, saying that it was “more likely than not that Mr. Schott was exposed to asbestos materials” while maintaining the GRC evaporator and that the asbestos-containing replacement parts would likely have been supplied by GRC as well.

Taking both sides into consideration, Robreno wrote that while there is evidence supporting the allegation that the decedent would have been exposed to asbestos-containing gaskets, packing and insulation, there is no evidence, however, from anyone with personal knowledge that the claimant was exposed to products manufactured or supplied by GRC.

During testimony, Lowell suggested that it was likely the replacement products came from GRC, but both Rueter and Robreno agreed that opinion is speculative.

“Therefore, even when construing the evidence in the light most favorable to plaintiff, no reasonable jury could conclude from the evidence that decedent was exposed to asbestos from original or replacement gaskets, insulation or packing manufactured or supplied by defendant such that it was a ‘substantial factor; in the development of his illness, because any such finding would be impermissibly conjectural,” Robreno wrote.

Lastly, Schott objected to Rueter’s summary judgment approval as to her design defect allegations, but Robreno supported Rueter saying that under maritime law, Viad is not liable for products the decedent may have been exposed to but weren’t manufactured by the defendant.

Judge rules for defendant in asbestos case on product identification grounds